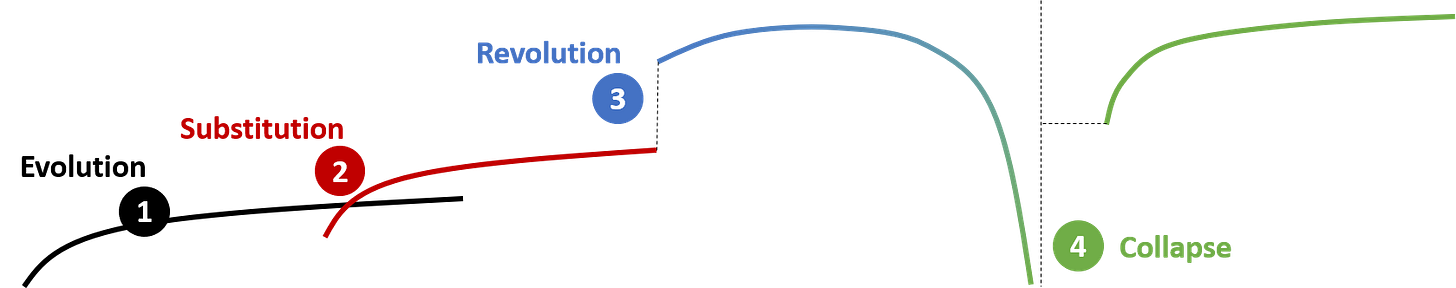

Change is a fundamental part of our lives. We see it happen in our environment, we undergo it ourselves, and we are also drivers of change. Change happens in the systems that govern our lives (e.g. political, financial, environmental), the organizations we belong to (e.g. the companies where we work, our families), or in ourselves (e.g. our tastes and preferences). The products we consume, or the companies we buy from, also change. And yet, despite this breadth of scenarios and contexts, there are only a few ways in which change occurs: by evolution, by substitution, by revolution, or by collapse.

Change by evolution happens through a series of transformations, often sequential and over an extended period of time, often for the better but sometimes for the worse. The evolution of natural species is the most frequently quoted example of evolution, but there are also many other examples in our daily lives. There is evolution in the products we use: cars become safer and more fuel-efficient, and computers run faster thanks to improvements in hardware and software. There is also evolution in human-related abilities: think of athletics and how marks and records are beaten every so often as a result of improvements in training and nutrition, among other. Political systems also change by evolution when laws are modified.

Change by substitution occurs when a given environment, product, or organization is replaced by a new one that fulfills the same or a very similar need, but in a better way (e.g. higher quality, lower cost, easier to use, etc.), and – very importantly – with a sense of continuity. The old becomes obsolete and disappears and the new takes over, but there is no void in the transition. Both alternatives even coexist for a period of time. Think of how digital cameras replaced film cameras, and in turn how smartphones have replaced digital cameras in everyday life. In both cases there has been change by substitution as a technology took over the previous one, and in both cases there has been continuity: people did not lose the ability to take pictures, they just transitioned from one technology to the next one. Smartphones have actually replaced many items that were part of our daily lives only a few years ago: alarm clocks, calculators, or flash lights. E-mail has replaced traditional mail, Whatsapps and similar text message services have replaced phone calls, and instant voice messages are replacing both for many users. In all these cases there was change, but also a continuity in our ability to perform the larger function.

Change by revolution occurs when an external shock causes a discontinuity, such that the old environment is overturned, and the new environment becomes the new normal. Both environments don’t coexist though: one takes over and in doing so cancels the other. Political revolutions are obvious examples: a social or a military ‘shock’ causes a fast change where the old system is simply suppressed and a new one is established, with no continuity in the fundamental institutions or laws, e.g. heads of state are simply deposed and constitutions derogated.

Finally, change by collapse occurs when an environment (or an organization, or a product), is unable to continue functioning. It ceases to perform or to exist without a ready replacement, and a period of void occurs until a new one emerges to take its place. Collapsed currencies generally fall in this change type. The value of the German Papermark deteriorated over several years during the Weimar Republic until the currency effectively collapsed. A new currency, Rentenmark, was introduced in Nov. 1923 at a rate of 1 Rentenmark = 1,000,000,000,000 Papermark. Hungary’s Pengö collapsed in 1946, after a year of steady loss of value, and Forint was introduced in August that year at a rate of 1 Forint = 400,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 Pengö.

Understanding these four ways of change is important to drive change efficiently: trying to drive change in the wrong way can lead to an overwhelming effort, and possibly low chances of success.

You are likely to fail if you try to fix (e.g. change by evolution) something that is so messed up that is beyond repair. Indeed, some situations are so messy that trying to fix them by incremental change, although theoretically possible, is a daunting task: you’re better off replacing or revolutionizing them. Symmetrically, you are likely to use unnecessary resources if you try to change by substitution (replace) something that only needs a small fix. If you are leading an organization, you will likely fail (i.e. lose credibility or followership from the organization) if you try to change by revolution and implement sudden, drastic change when your organization only needs a few tweaks. Of course, you may unwillingly drive an organization to collapse if you fail to drive timely change in any of the other manners. But also, in extreme cases organizations are in such poor shape that not even a revolution can save them, and the only way forward is to let them collapse while working on an alternative.

These four modes of change explain for example why dysfunctional political systems are so difficult to change: revolution and collapse are too painful and even violent, hence bad options. Substitution is unlikely if not plainly impossible: it’s improbable that two systems will temporarily coexist so that one can replace the other with some degree of continuity. The only option left is evolution, but if the system is too dysfunctional, the effort resembles undoing a chaotically tangled bunch of threads: possible but frustrating and time-consuming. For those familiar with the political Transition in Spain after the death of dictator Francisco Franco in 1975, that is what makes it such an extraordinary achievement: the system itself succeeded to evolve from dictatorship to democracy through a series of changes driven from within (not a replacement of a system by another), surviving a coup (i.e. a revolution in the aforementioned sense) and avoiding a blunt collapse.

In short, there are infinite change situations, but only a few paths to undergo and drive change: by evolution, by substitution, by revolution, or by collapse. Next time you need to drive change, ask yourself first which of them is the one that best serves for the very context you’re facing.